The next two weeks will largely consist of a series of back-to-back train and bus rides. We will dutifully report everything here as we have been doing so far, but let’s be honest: it won’t be the most exotic part of the trip. So, in a last ditch attempt to keep our faithful readers reading until the end, here is a final slice of Asian exotica to (hopefully) delight and entertain.

Having reached Tashkent (see last blog post) we set out to explore Uzbekistan’s famous Silk Road cities: Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand.

Our first stop was Khiva, situated in the west of Uzbekistan in the middle of the Kyzylkum desert. There really is nowhere else quite like it: a perfectly-preserved medieval desert city complete with mud ramparts. To our limited minds the grand exotic architecture evoked Aladdin, magic carpets and camel trains, while the maze of dusty lanes and mud-built houses felt like a scene from the nativity.

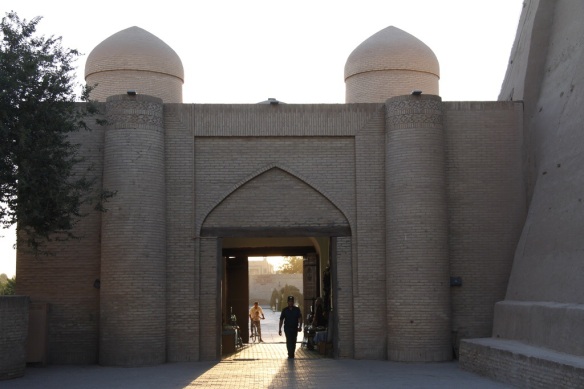

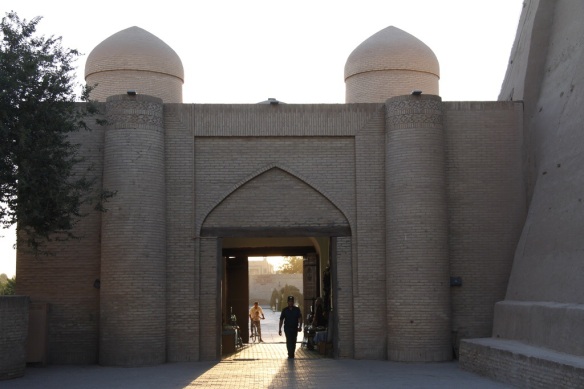

The amazing thing is that Khiva was still a fully-functioning independent “khanate” right up until the early twentieth century. Convicted criminals were still being tied up in sacks and thrown from minarets, while the historically-thriving slave bazaar didn’t completely peter out until the Bolsheviks took power in the 1920s. We could clearly make out the alcoves in the city’s east gatehouse where newly captured Persian or Russian slaves were displayed for sale.

After being annexed by the Russians in the late nineteenth century, Khiva managed to survive for a few more decades before it’s powers were taken away and it’s streets emptied of citizens. Today it is a museum: Khivans themselves live in a new town outside of the walls, giving the old city a rather deserted atmosphere, heightened during our visit due to the extreme summer heat and consequent lack of visitors.

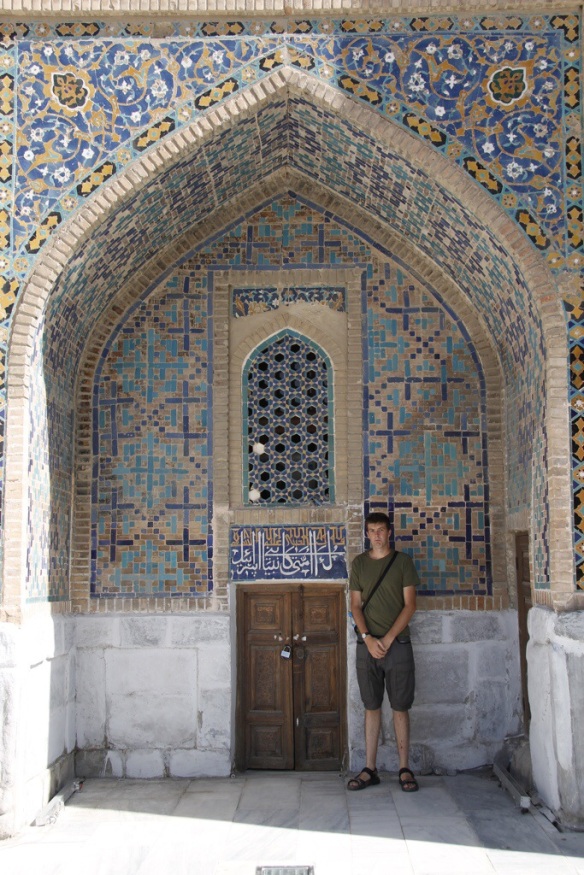

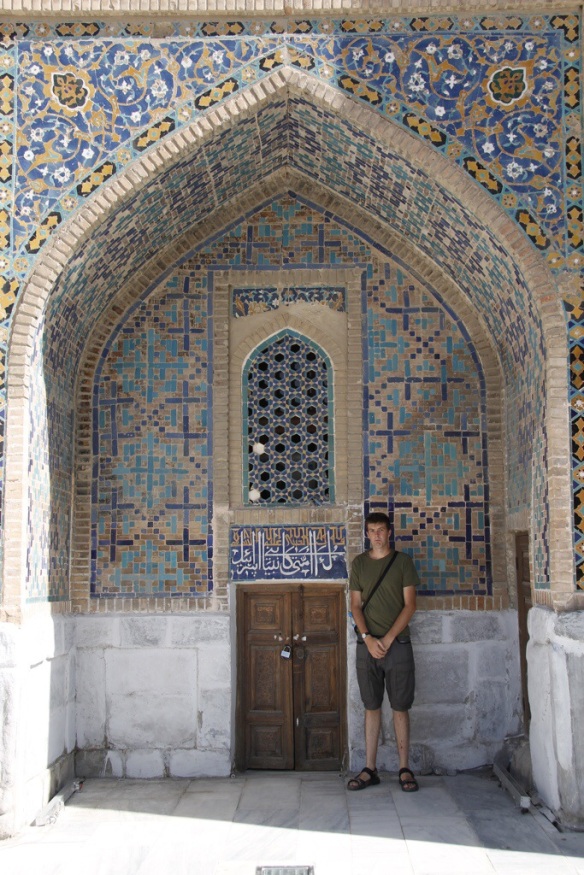

The tile work here is stunning, whether adorning a minaret, decorating the interior wall of a private mosque or throne room, or livening up the gates of austere sand-coloured medressas (Islamic places of learning). The minarets were the absolute highlight for us, probably due to the effect of bright blue tiles against the brown and grey desert scenery. One of the best things about Khiva is that you can stay in a traditional Khivan home within the city walls and enjoy the all of this after the tour groups and hawkers have gone home!

Above – Heather views Khiva from a watchtower on the mud walls

Above – Heather views Khiva from a watchtower on the mud walls

Below – A policeman enters the west gate of the old city

Above – The Kutlimurodinok Medressa

Above – The Kutlimurodinok Medressa

Below – Traditional blue and white tiling in the Tosh-hovli Palace (spot the accordion)

Above – The Islam-Hoja minaret

Above – The Islam-Hoja minaret

Below – Traditional musical instruments for sale on a Khivan street

Above – Little(ish) and large: a Medressa in front of the colossal tiled Kalta Minor minaret

Above – Little(ish) and large: a Medressa in front of the colossal tiled Kalta Minor minaret

Below – Relaxing on the mud roof of our guesthouse at sunset. Khiva’s medieval mud-built walls are behind us

Next we made our way east through some of the driest and hottest landscapes we have seen on this trip – to the holy city of Bukhara. Bukhara is larger than Khiva and historically more important as a place of Islamic pilgrimage, religious education and Silk Road trade. The buildings are grander and more spread out, interspersed with scrappy but interesting bits of old town where actual Bukharans still live and work.

Thankfully we didn’t get the same welcome as a pair of British travellers who preceded us back in the 1840s. Colonel Charles Stoddart and Captain Arthur Conolley, amongst the very few Europeans who had seen legendary Bukhara at that time, were kept in the infamous ‘bug pit’ for months with only rats, lice and cockroaches for company (in a move that would later inspire the makers of I’m a Celebrity, Get me out of Here). Finally they were dragged out in front of the Emir’s subjects, made to dig their own graves, and then beheaded. In short, Bukhara’s despotic Emirs were famous for their elaborate and sadistic punishments and, like Khiva, their economic reliance on the slave trade.

Many of the individual buildings in Bukhara clearly surpass anything in Khiva both in terms of grandiosity and scale. But we felt that some of the renovations and more aggressive attempts to make the town tour group-friendly had sapped some of its soul. A good example is the famous Lyabi Hauz public square. The space has been desecrated in recent years by fake plastic camels, a bouncy-castle Medressa, a chintzy scale model of Bukhara (in use as a floating duck house), and a series of gaudy plastic storks adorning the ancient mulberry trees (Bukhara’s real-life storks all left the city after the Soviets drained the canals and pools). It becomes quite difficult to appreciate the elegant architecture in amongst all this cheap crap – to the extent that we barely took any photos in that area at all.

On the other hand, some of the other buildings in Bukhara are just spectacular. Immaculately preserved covered bazaars, beautiful medressas (some of which are still in use), and of course the Kalon mosque and minaret. And it didn’t take much to escape touristville. One morning, in search of fresh fruit and vegetables, we made our way to a large modern bazaar in the Russian part of the city. Within five minutes a sweet lady who was at the same fruit stall as us had insisted on paying for our bag of plums in a Ramadan-inspired act of generosity. She also filled our hands with fruit pastilles and tried to give us her bag of recently-purchased apples!

Above – The Mir-i-Arab Medressa

Above – The Mir-i-Arab Medressa

Below – Char Minor

Above – Blue dome of the Kalon mosque

Above – Blue dome of the Kalon mosque

Below – Tile work of the Nadir Divanbegi Medressa, depicting a pair of peacocks holding lambs either side of a sun with a human face

Above – Bukhara at dusk

Above – Bukhara at dusk

Finally, we took the “golden road to Samarkand”. Well, we took the train. Samarkand has to be the most evocative Silk Road place name of them all, and in fact it’s where it all started for this region. Tamerlane, responsible for restoring the glories of Ghengis Khan’s Mongol Empire, was born here in 1336. His descendants went on to conquer much of Central Asia and Northern India and Samarkand was, for centuries, their capital.

Today Samarkand is a fairly big city by Uzbek standards, with pleasant green spaces and a Russian town that’s actually nice to be in. It’s size makes it feel completely different to Khiva or Bukhara, though unfortunately city planners have been busy erecting ugly walls to separate the big tourist sights from the fascinating and still lived-in old town that surround them. It kind of feels like custom-made fitted wardrobes but for a city.

The most famous sight here and anywhere in Central Asia is the Registan, a huge public square flanked on three sides by some of the oldest, largest and most opulent Islamic buildings anywhere on the planet. Unfortunately we found our visit to be quite flat, mainly because the authorities have allowed tacky tourist shops to fill all of the nooks and crannies of these amazing buildings. Aggressive sales tactics meant that we couldn’t ignore this – some shops had even displayed their wares in cabinets around exhibits within the museums!

Elsewhere in the city we did like the Gur-i-Amir mausoleum for its blue-fluted dome and for the fact that it was just two minutes walk from our guesthouse. The Shah-i-Zinda cemetery was also a fascinating and beautiful place to walk – though not for long in this heat. As you will see from the photos there are actual normal people living here as well, which means that there was a bit more going on at night and even some tasty food options (a rarity in Central Asia).

Above – Tiled facades of the mausoleums at the Shah-i-Zinda cemetery

Above – Tiled facades of the mausoleums at the Shah-i-Zinda cemetery

Below – Interior of one of the Shah-i-Zinda mausoleums

Above – The Sher Dor Medressa on The Registan (the tigers are actually lions)

Above – The Sher Dor Medressa on The Registan (the tigers are actually lions)

Below – Enjoying some shady downtime in a Medressa courtyard

Above – James struggles to come to terms with one aspect of the local Islamic architecture

Above – James struggles to come to terms with one aspect of the local Islamic architecture

Below – The spectacular Gur-i-Amir mausoleum

Above – Heather enjoys a rare injection of vitamin C in the form of tomato salad. We also have meat dumplings (manty), noodle soup (laghman) and the ubiquitous pot of black chai

Above – Heather enjoys a rare injection of vitamin C in the form of tomato salad. We also have meat dumplings (manty), noodle soup (laghman) and the ubiquitous pot of black chai

Below – The locals enjoy a classy sound and light show at the fountain

More photos (mostly of buildings)…

Khiva: http://www.flickr.com/photos/100848910@N08/sets/72157645503789012

Bukhara: http://www.flickr.com/photos/100848910@N08/sets/72157645538568906

Samarkand: http://www.flickr.com/photos/100848910@N08/sets/72157645596023362

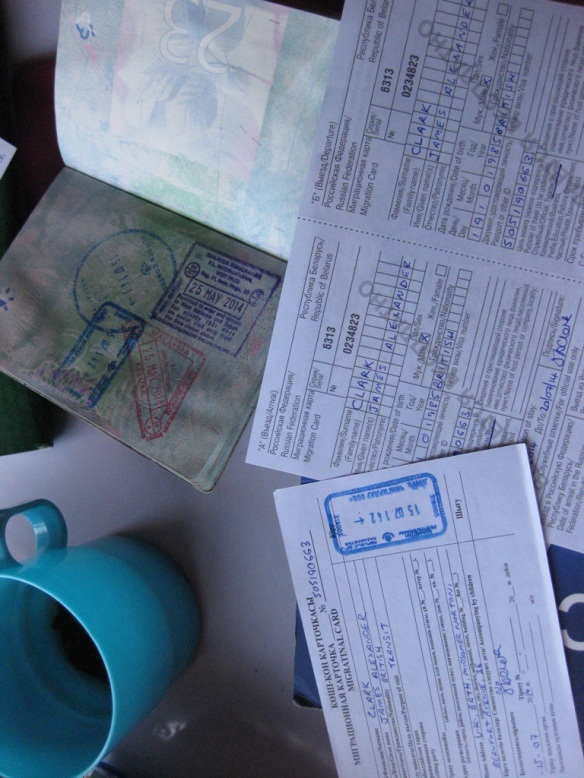

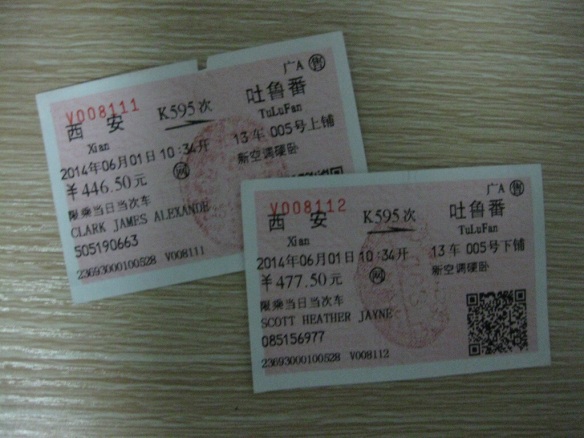

n.b. We’ve actually got about 1,500km of Asia still to cover but we won’t have much of an opportunity to immerse ourselves in it as we’ll be stuck on a train. What the hell you do with four days and three nights on a single train will be the subject of our next blog post, by which point we will hopefully be in European Russia!